The Future of Sourcing.io

by Alex MacCaw

I'm really excited to announce the next chapter of Sourcing.io under the management of the good folks behind Underdog.io. For me, Sourcing.io was always a labor of love and never got the attention it deserved. The idea has so much potential; recruiters are crying out for help finding the right candidates, and Sourcing.io offers a way to do that using your team's existing social connections. It deserved a good home.

But I knew it couldn't just be any old home - it had to be with a group of people who really understand technical recruiting and who have a big vision for Sourcing.io's future. Underdog.io has been growing like crazy in NYC and SF, and when they approached me about acquiring Sourcing.io to complement their existing product, I know it was the perfect match. They truly understands hiring and there's no doubt in my mind that Sourcing.io will go to exciting places.

JavaScript MVC Style Guide

by Alex MacCaw

Over the years I've come up with a few rules for MVC web apps that have served me well and kept large codebases from descending into chaos. While the terminology may differ, these rules should hold true for most client-side MVC frameworks such as Backbone and Ember.

Some frameworks have different naming MVC conventions, and slightly different takes on separating concerns. In this document, controllers are the glue between models and views, views are HTML templates and models purely deal with data storage, retrieval and decoration. This fits well into the Backbone & Spine terminology. Ember has similar conventions, but goes a step further in separating out DOM access from controller logic.

Controllers

- Controllers are the glue between views and models. Most of their logic concerns event management. Keep controllers skinny.

- Any communication between children and parent controllers should use events (do not pass an instance of the parent around).

- Should only know about sub controllers.

- Should be scoped to a single element, and not access or alter other parts of the DOM.

- Should have a unique class name, and all CSS relevant to this controller should be namespaced by this class name.

- Should work even if their element is not appended to the DOM tree. This is useful for testing and demonstrating the controller is properly scoped.

- Should be testable by firing events programatically on their sub elements.

- Should be able to be re-rendered at any time without adverse effects.

- Should not use the DOM to store state — keep any view specific state stored as instance properties in the controller.

Views

- Should be logic less except for flow control and helper functions.

- Should be passed all the data they need to render directly. It should all be available in the current scope.

Models

- Should purely be concerned with data, manipulating data and decorating data.

- Should never access controllers or views.

- Should never access or return DOM nodes.

- Should only access or require other models at runtime.

- Should abstract away XHR connections from the rest of the application.

- Should contain all data validations.

Routers

- Should be as logic-less as possible.

- Should not know about or access the DOM.

Global state

- Should be kept to a minimum as it arguably violates MVC. You can't get around it for some things though, like the current user, current view, CSRF token etc.

- Should never be stored in global variables.

- Should all be stored in one place (such as a singleton instance of a model).

Modules

- You should always use a module system, whether it's CommonJS, AMD, ES6 modules, or something equivalent.

- Never set or access global variables.

Pull requests accepted

A style guide should be a fluid document and evolve as your team encounters specific problems and gains experience. Its main purpose is to keep the codebase consistant and clean. If you have any suggestions for this document, tweet them to me at @maccaw.

The most valuable email I ever automated

by Alex MacCaw

Email runs everything at Sourcing.io and we get email updates for every sign up, upgrade, cancellation, and other major user interactions. Essentially we use email like a poor man's logging system which has the major advantage of letting me see all a customer's actions, and any emails we've corresponded with them, all in one place.

Whenever we have subscription churn I reach out to the customer in person, asking if there's anything we could do to improve the product and kept their custom. This short exit-interview has turned into one of our most valuable sources of feedback we get.

The email goes something like this:

[Subject] Sourcing.io & Sprockets

Hi James Smith,

We're sorry to lose you as a customer.

Do you have any thoughts or feedback on Sourcing.io?

Anything we could improve upon?

Thanks,

Alex

Over time as the business has expanded to hundreds of paying customers I've ended up automating the sending of this email. Naturally I'll always address any follow ups in person but automating the initial email makes it a bit less labor intensive. We have enough information on users to create a convincing email with a custom subject and first name, and then we use Resque Scheduler to send the email about two hours after accounts are deactivated.

This email has a surprisingly high response rate and the feedback we get is incredibly valuable to the business. The reasons people give for canceling range from the product is too expensive, to the fact that they're not hiring anymore, to a specific feature we're missing.

Suggestions from this email go straight back into the product cycle and we make sure to keep track of who requested what so we can follow up whenever that feature is implemented.

The other aspect from this email is that it's a good source of sales. Often we can encourage customers to re-activate their accounts or introduce us to their recruiting team. It's probably the most valuable email we send.

Improving paid conversions

by Alex MacCaw

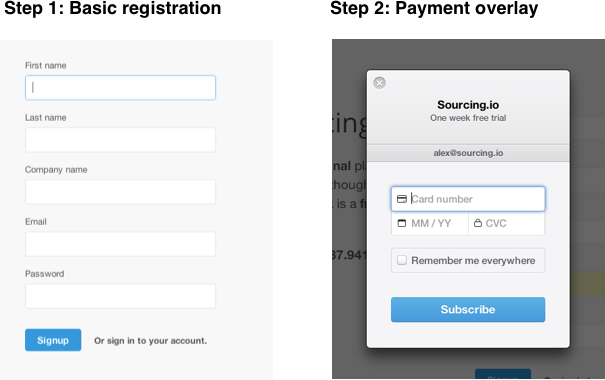

When we initially designed Sourcing.io we decided to require a credit card for the signup process even though we were offering a weeks free trial. This was for a few reasons, but mainly because we felt our data was too valuable to give away for free and requiring a credit card showed commitment while striking a good balance between charging up front and a freemium model.

Additionally we had some compelling data indicating that requiring customers to enter their credit card dramatically altered their perception of the product, and made them more likely to pay in the long run. That's a subject for another post though.

There's no doubt about it though, requiring a credit card up-front lowers your sign-up conversion rate. Since we were using the Stripe Checkout (which I had the pleasure of working on whilst at Stripe), we had no choice but to split our signup process into two steps — one step to enter your account information such as name, password etc, the other step to open the Stripe Checkout overlay and collect payment information.

Clearly we were going to get some people dropping off the registration form between the two steps when they realized they need to enter some credit card information. What we realized though, was that this was actually an excellent sales opportunity.

We started to record the partially filled in form, and send an automated email to us whenever a user dropped off registration before the second step. We call these draft signups. Once a day, we manually go through these draft signups and reach out individually to companys who look like a good fit for Sourcing.io, offering them a free trial without having to provide a credit card.

In other words, we get to have our cake and eat it. We get to keep the upfront credit card without lowering the conversion rate too much. We also get to start a valuable conversation with customers we'd otherwise have lost. The results speak for themselves: we've converted countless draft signups into paying customers and many of our biggest clients were converted via this process.

New features: Assign candidates and more

by Alex MacCaw

We've just shipped two new features for Sourcing.io that should make it much easier to manage candidates and reach out to them.

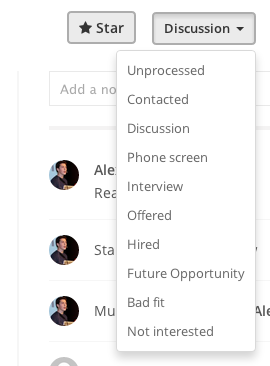

Setting a candidate's status

Often it's nice to track a candidate through the hiring process, and if someone in your team has already reached out. Sourcing.io now lets you set and filter by a candidate's 'status'. For example, you can set a candidates status to 'Contacted' or 'Discussion'. This status is reflected globally for all users across your account.

Assigning candidates

You can assign a candidate to yourself or a specific person in your team. We also allow you to filter by candidates assigned to specific users.

As always, feel free to reach out to us if there's a particular feature you need that's missing.

Visualizing Design Evolutions using Git

by Alex MacCaw

With technologies like Git, we can easily access the history of a repository, and see how the code is build up over time. I've been wondering if we can do the same with designs, visualizing the evolution of an application from a visual perspective.

With that in mind I wrote a script that checked out every commit of a JavaScript app I wrote called Stylo, and took a screenshot using WebKit2png. Then I spliced all those images together and the result is the video below.

My design process is pretty iterative, and I'm constantly tweaking colors and positions to see what looks good. As well as being an interesting perspective into an applications evolution, I think this is also useful from a QA and regression testing perspective.

for commit in $(git rev-list master)

do

$(git checkout $commit)

$(webkit2png public/index.html)

done

Unfortunately this particularly method of generation visualizations is probably not going to be ideal for most applications. Stylo is a static JS app, and therefore I don't have to worry about database migrations or other state that's not synconrized with Git commits. The ideal solution is probably taking a screenshot with a pre-commit hook.

Engineer's Guide to US Visas

Update: We've partnered with Bridge to simplify visa process for employers. Visit their website to learn more.

Gather a group of foreigners together in San Francisco, and the topic of conversation invariably turns to visas and immigration. For many of us just getting to America is a feat in itself. Overcoming the regulation, hurdles and bureaucracy that encompasses the US visa system is a shared and painful experience we can all relate to.

Five years ago, when I was working back in England, I wanted nothing more than to emigrate and join a tech startup in San Francisco. The trouble was I had no qualifications, no degrees and no connections. It's only through a great degree of persistence, determination, and the support of some wonderful people that I'm living out in SF.

At that time I would have given anything to have had more information about the US visa system. Unfortunately, there's not much out there — especially any geared towards engineers. The aim of this guide is to fill some of that knowledge gap, and help other aspiring people reach the states. This guide specifically focuses on employees; I'll be writing a more founder centric one in the future.

Education

There's no sugar coating it; having a degree in computer science, or a closely related field, is really going to help you with getting a US work visa. The system is setup in a one-size-fits-all manner which, while understandable, definitely causes problems in our industry. It can leave engineers in the nonsensical position of having an excellent job offer, but not being able to fulfill the education requirements to obtain a work permit.

People in our field have a hodge podge of different backgrounds, and it's not uncommon for a competent software engineer to have either studied a completely irrelevant degree, or to not have attended higher education at all. That said, while having a computer science degree will help, don't despair if you're not in that position — there are other ways to qualify.

Representation

You will need legal representation. Usually the company you join will organize this, but in case you're looking for recommended immigration attorneys in San Francisco I've listed some at the end of the article. You should get advice from a lawyer before making any decisions. None of this article is to be construed as legal or financial advice.

Companies

Most tech companies I've encountered are interested in sponsoring visas if they can afford to. The demand for engineers in the US is such that the local talent can't satisfy it.

A visa can cost companies anywhere between $2,500 to $10,000 in legal and USCIS fees to sponsor. Compared to an engineer's salary, this isn't usually a problem for companies — especially if they've raised some outside capital.

What is a problem to companies though, is the amount of time it takes to prepare and process a visa. I find that usually any objections to sponsoring a visa boil down to the time costs, rather than anything else. This is especially true for H-1Bs, which can take the best part of a year to process depending on when you apply.

Interviewing

If you're a remote candidate, companies will often apply a higher barrier of entry for phone interviews before they move you to an on-site. This is understandable since they're the ones footing the bill to fly you out and put you up in a hotel. Unfortunately, as a candidate, this might decrease your chances of an offer.

It's for this reason I suggest coming out to SF on your own accord, staying for a short while, and lining up a bunch of interviews with all the companies you're interested in. The other advantages of this approach is that after an interview or two you'll get used to the general format and probably perform better. If you do get multiple offers, you'll be in a much better negotiating position.

Once a company is interested in hiring you, it's time to look at what kind of visa you qualify for.

Visa types

There are various different types of visas, and which you apply for depends on your education, nationality and specific circumstances. A few visas can be self-sponsored, but most of them need to be sponsored by a company in the US. In other words, you have to have a job offer to get the visa.

Some visas are dual intent (meaning you can have intent to stay permanently), and some of them are only meant to be temporary. This is an important distinction to make, and will affect your ability to get a green card in the future.

If you're not on a dual intent visa then you may be asked to prove that you have significant ties to your home country, and no intent to reside in the US permanently or apply for a green card.

The main visa types are:

- E-3 visa for Australians

- TN visa for Canadians and Mexicans

- H-1B visa for degree holders

- L-1 visas for inter-company transfers

- J-1 visa for internships

- F-1 visa for students

- O-1 visa for extraordinary ability

E-3 visa for Australians

Australians with a Bachelor's degree (in the relevant field) can qualify for the E-3 visa which, compared to other visas, is incredibly straightforward. You'll have to apply outside the US at one of their embassies in Australia.

The caveat to this visa, is that it isn't dual intent. This means you can't apply for permanent residency via a green card whilst on it.

| Dual intent | No |

| Sponsorship | US Company |

| Requirements | Specialty occupation (i.e. software engineering), a Bachelor's degree and Australian citizenship |

| Duration | Indefinitely renewable (in two-year increments) |

| Processing time | Weeks |

| Spouses | May work under the E-3D visa |

TN visa for Canadians and Mexicans

Canadians and Mexicans with Bachelor's degree in the relevant field (i.e. computer science) can qualify for the TN visa.

If you qualify, it's usually a fairly straight-forward visa to get. In the past you'd have to turn up at the border with all your documentation and hope for the best — they'd make the decision on the spot. Fortunately this policy has recently changed, so you can now apply for TN visas in advance.

The USCIS has a white list of acceptable professions under the TN visa. While programmers aren't included, software engineers are. If you don't have a degree, but you are an engineer, you may have luck going with the 'Management Consultant' route. Five years of 'equivalent work experience' can also help you obtain this visa category.

While the TN visa is similar to the H-1B, it isn't subject to an annual cap and therefore may be easier for Canadians to get. The important difference is that the T1 isn't dual intent, and you therefore can't apply for a green card while on it.

TN visas are specific to the company, and can't be transferred without re-applying. TNs aren't technically renewed after three years — you essentially have to re-apply for a new one. This lends a degree of unpredictability to this visa as it could get rejected any time you renew it; especially if it appears you are not in the US on a temporary basis anymore.

| Dual intent | No |

| Sponsorship | US Company |

| Requirements | Specialty occupation (i.e. software engineering), a Bachelor's degree in computer science and Canadian or Mexican citizenship |

| Duration | Technically indefinitely renewable (in three-year increments). In practice, it's not so easy. |

| Processing time | Weeks |

| Spouses | May enter, but not work, under the TD-1 or TD-2 |

There are a bunch of great guides which explain the process in more detail.

H-1B visa

The H-1B is the classic visa that many foreigners apply for. If you hold a degree and you're not Canadian or Australian, it's likely that your company's lawyer will suggest this one.

If you do not have a degree, than you may still be able to qualify if you have 12 years of work experience in a field related to the H-1B position.

A H1-B visa only lasts 6 years, and can't be renewed. However, H1-Bs are renewable yearly beyond the 6th year if your Green Card request is being processed.

The biggest drawback with this visa is the annual quota of 65,000, which invariable gets used extremely quickly. There are an additional 20,000 lots reserved for Master's degree holders. The USCIS renews the quota on the 1st of April, the floodgates open, and it's a mad scramble to get your application in. In 2013, the whole year's cap was reached in just 5 days. The kicker is that if you're lucky enough to get approved you can't actually move to the US and start work until October 1st of that year.

If your job doesn't fit into that time-frame, tough luck. As you can imagine this is inviable for many startups, and they will simply refuse to sponsor H-1Bs.

If you're a citizen of Singapore or Chile then you can apply for the H-1B1 visa; a derivation of the H1-B that doesn't have the quota problems.

| Dual intent | Yes |

| Sponsorship | US Company |

| Requirements | Specialty occupation (i.e. software engineering) and a Bachelor's degree, or 12 years experience |

| Duration | 3 years, extendable to a maximum of 6 years |

| Processing time | Many months |

| Spouses | May enter, but not work, under the H-4 |

L-1 visa for inter-company transfers

If you've worked for the company in a foreign subsidiary for at least one year in the preceding three years, you may be eligible for a L-1 visa. When the H-1B cap is reached, large companies like Google often look to L-1s instead, moving new employees to their Canadian offices for a year to make them eligible.

The foreign subsidiary must be related to its US counterpart in one of four ways: parent and subsidiary, branch and headquarters, sister companies owned by a mutual parent, or 'affiliates'.

It's a fairly straightforward visa to get if you qualify, and has the added bonus of being dual intent.

| Dual intent | Yes |

| Sponsorship | US Company |

| Requirements | You've worked at the company for at least a year prior |

| Duration | Depends on the country you're from. Usually from two to five years. With extensions, the maximum stay is seven years. |

| Processing time | 2-3 months |

| Spouses | May enter and work under the L-2 visa |

J-1 visa for internships

Many major tech companies and startups have internship programs designed for sponsoring J-1 visas. This is a temporary visa designed for exchange students to come to the US and enroll in an internship program. It's not uncommon for software engineers to use this route, especially if they've just graduated, as this visa is easy to obtain and relatively flexible.

You can get a J-1 for an internship or training period if you match one of the three categories:

- Students (college/university)

- Recent graduates

- People with five years or more work experience

There's slightly different variations of the visa depending on which category applies to you. It's worth pointing out that this visa is not intended for ordinary employment, but rather just for training.

A third party, called a sponsoring organization, is also required to file the visa. Two good examples of these are CIEE and Cultural Vistas, but a complete list of J-1 sponsors is available on the State department's website. They will review your application and grant the DS-2019 document which permits you to intern.

There's no limits to how many J-1's a person can have during their lifetime. You can get an extension to them, as long as that extension is within the maximum time limit. You can't transfer J-1s between companies, you have to re-apply. Once your J-1 expires, then you'll need to stay in your home country for two-years unless you receive an exemption (relatively straightforward in the tech sector).

| Dual intent | No |

| Sponsorship | US Company plus sponsoring organization |

| Requirements | Student, recent graduates, or five years of work experience. |

| Duration | Maximum of one year (depending on profession) |

| Processing time | 1-2 months |

| Spouses | May enter and work under the J-2 visa |

F-1 visa for students

Students at US schools on F-1 visas may apply for Optional Practical Training (OPT), and be authorized to work for a year in a industry related to their area of study. You can extend this OPT by an additional 17 months if you're getting a Bachelors in engineering.

The F-1 is a good choice if you're just getting started in the technology sector, and potentially a stepping stone to more permanent visas like the H-1B. Your university should be able to provide you with more information about this visa.

| Dual intent | No |

| Sponsorship | N/A |

| Requirements | Students or recent graduates of a US university |

| Duration | One year. Extendable by an additional 17 months |

| Processing time | Weeks |

| Spouses | May enter, but not work, under the F-2 visa |

O-1 visa for extraordinary ability

The O-1 visa is for exceptional candidates, usually reserved for people who have had significant impact upon their industry. The full title, I kid you not, is aliens of extraordinary ability.

The O-1 is increasingly popular, especially with candidates who can't qualify for other visas because they don't have a degree. It's a pretty tough visa to get though, and you need to fulfill at least 3 of the 8 criteria. I've paraphrased some of them below:

- Published material about you in major publications or media

- Judging the work of others, either individually or on a panel

- Original contributions of major significance to the field

- Authorship of scholarly articles in major publications or media

- Performance of a leading or critical role in distinguished organizations

- High salary in relation to others in the field

Receiving press coverage, publishing a book, raising investment, or demonstrating significant contributions to your industry can all help your case. As well as the evidence, you have to get 8 to 10 prominent and accomplished people to write letters petitioning your case.

If you do qualify, it's a great visa to get. It's flexible, indefinitely renewable, easily transferable and potentially a stepping stone to the EB1 green card.

| Dual intent | Yes |

| Sponsorship | US Company |

| Requirements | Meet at least 3 out of the listed criteria |

| Duration | 3 years, indefinitely renewable |

| Processing time | 1-2 months |

| Spouses | May enter, but not work, under the O-3 visa |

Spouses

Unfortunately with many visa types, while spouses are let into the country as your dependents, they are not authorized to work. Some visas allow them to study, but there are some restrictions on that too.

For married folks, a huge question is what will the spouse do. Volunteer, start their own business, work remotely for a company back home or do consulting via a home company are some of the options. Many choose this time to have their kids who, if born inside the US, will receive US citizenship.

Expedited processing

You can pay premium processing for most of these visas, and while it's usually a few thousand dollars more, it's absolutely worth the price in terms of your time. You'll get an answer from the USCIS in the order of weeks, rather than months or years.

Green card

A green card, or permanent residency, lets you live and work in the US on a permanent basis. In practice, it holds many of the same benefits of being a citizen (apart from being able to vote).

While you're seeking your employment based green card, you will be lumped into three categories:

- EB-1: workers of extraordinary ability

- EB-2: PhDs / masters / 5 plus years experience in field

- EB-3: Bachelors degree / less than 5 years experience

Within the EB-1 category, there are three sub-categories: EB-1A workers with extraordinary ability; EB-1B outstanding professors and researchers; and EB-1C multinational executives and managers. If you're on the O1, than the EB-1A category is the most natural transition to a green card (although the requirements are much more stringent). If you're on a L-1A inter-company transfer visa than the EB-1C path to a green card is the most straightforward.

Many of the dual-intent visas, such as the H-1B, are a stepping stone to getting a green card. It's unlikely that you'll qualify for a green card off the bat though without spending some time in the US on a working visa. As such, green cards are beyond the scope of this article.

Diversity Visa Program

The Diversity Visa Program, or Green Card Lottery, is a visa designed to diversify the immigrant population in the US. Visa quotas are alloted to countries based on how many immigrants they sent to the US in the previous. If a country has sent more than 50,000 immigrations in the last five years, they're not eligible for this visa.

Most of Europe, except the United Kingdom, is eligible. Australia and New Zealand are also eligible. If you come from a territory that's eligible, than this is a good way to potentially get a green card quicker. Visas are handed out to a random drawing of applicants. The higher the quota of your country, the greater your chances. Spouses can apply separately to double your chances.

If you lose in the lottery, they'll refund the fees. One caveat to bear in mind is that applying for this visa shows intent, which may disqualify you for visas in the future which aren't dual intent, such as the B-1 & B-2 visitor visas.

Once you have a visa

You've got your visa, moved to the US, and you're about to start your job. What other things do you need to know?

To get paid you'll need a social security number (SSN), which you can apply for at your local Social Security office. Wait at least 10 days after you've entered the country to apply for this; the various departments involved need a little time to sync up, and applying too soon can significantly delay your application.

Getting a bank account is fairly straightforward, and most don't require a SSN. You should get this as soon as you can, because without one it's pretty impossible to do anything else.

Next you'll probably want a phone. Unfortunately, chances are you haven't got any US credit history, and most phone companies will refuse to let you sign up to a contract without a hefty deposit. Get used to this; you'll probably have to pay a few more month's rent as deposit when renting a place too.

Recommended lawyers

The following immigration attorneys I've either had to the pleasure of working with, or they've been highly recommended by friends. Needless to say they're all excellent.

Conclusion

Make no doubt about it — getting a US visa is extraordinary difficult, even for really qualified individuals who are going to contribute a lot to the country in terms of engineering and taxes. However, in my experience, it's absolutely worth it. Moving here was the best thing I ever did. It's an incredible country, and the opportunities here in tech are second to none.

If you're planning on starting a company, rather than getting a work visa, things are going to be even more tricky. I'm planning on writing another article focused towards entrepreneurs in the near future. For now, the USCIS has a good guide. Good luck!

As with all information on the internet, take this with a pinch of salt and get advice from a immigration attorney before making any decisions. None of this article is to be construed as legal or financial advice.

Introducing Connections

by Alex MacCaw

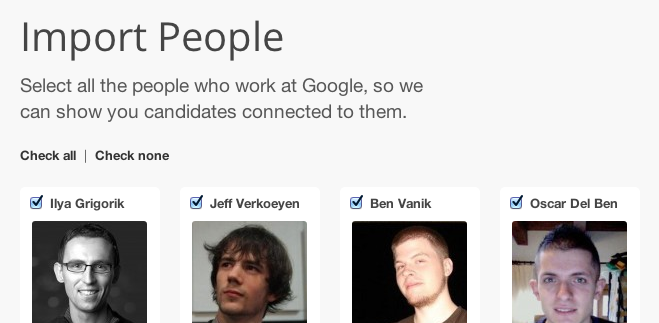

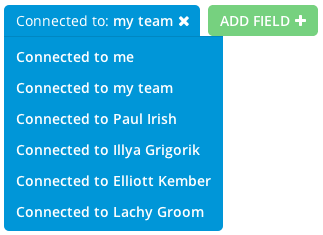

I'm excited to announce we've just shipped one of our most requested features: batch importing of connections. Now you can import your whole team's social connections without having to ask them all to individually sign up to Sourcing.io and link their accounts.

When you're creating a Sourcing.io account, we suggest to you people who we think work at your company. You can then bulk import them and all their Twitter connections.

What's great about this is that as hiring manager you can import your whole team's social connections in one click, and start looking at software engineers in your extended social network. Then, when you've found a good candidate, you can ask whoever knows the candidate inside your company to reach out. We've found that referrals are always the highest converting forms of recruiting.

Additionally we also allow you to import one-off individual Twitter accounts. For example, say you have an investor who is quite willing to make introductions to people they know, you could add their Twitter account to Sourcing.io and filter by any candidates who follow them.

We've got lots more features like this coming your way in 2014! If there's something you're looking for in particular, or if you've got any feedback, then please get in touch.

Structuring Sinatra Applications

by Alex MacCaw

I love Sinatra. I use it for practically everything. For me, Sinatra has the perfect blend of simplicity and abstraction. I can understand the full stack, dip into the source when I need to, and extend the framework how I see fit.

However the bare-bones nature of Sinatra can come at a cost. Sinatra leaves much more of the decision making around your application's structure, layout and libraries up to you. This can be a bit daunting if you're just getting into Ruby web app development, which I think is one of the reasons why Sinatra is mainly the realm of more experienced developers looking for a bloat-free alternative to Rails.

Over the years I've put together a few conventions that I share between all my Sinatra apps, and in this article I'm going to elaborate on those. I've also created a gem called Trevi which, if you want to follow this approach, will go ahead and do all the manual lifting for you by generating a Sinatra scaffold.

$ gem install trevi

$ trevi brisk

create brisk

create brisk/.gitignore

create brisk/Gemfile

create brisk/Procfile

create brisk/Rakefile

create brisk/app.rb

# ...

run git init . from "./brisk"

run bundle from "./brisk"

Bundler

First we're going to setup Bundler and the gems our application is going to require. Run bundle init to create our Gemfile. It should look something like the following:

source 'https://rubygems.org'

ruby '2.0.0'

gem 'sinatra', require: 'sinatra/base'

gem 'erubis'

gem 'rake'

gem 'thin'

We're requiring sinatra/base, rather than plain sinatra, since we're using the modular Sinatra style, which essentially means we're using modules and namespaces rather than the classical style of putting everything inline. There's nothing wrong with the classical style for simple applications, but if you're planning on building anything complex I'd definitely go with modular.

Run bundle install to generate our Gemfile.lock.

App

Next let's create a namespace for the application, which everything will live under. Don't spend too much time deliberating over the name of the app — just choose an internal code name for the namespace (for example, Brisk). Let's create the application's initial file called app.rb

require 'rubygems'

require 'bundler'

Bundler.require

module Brisk

class App < Sinatra::Application

configure do

disable :method_override

disable :static

set :sessions,

:httponly => true,

:secure => production?,

:expire_after => 31557600, # 1 year

:secret => ENV['SESSION_SECRET']

end

use Rack::Deflater

end

end

In this file we're first requiring all our gems via Bundler, then we're setting up a little Sinatra application. Notice that we're enabling sessions and disabling static files.

Next up we need to create a config.ru file for rack. This will just require our app.rb file, and mount Brisk::App.

require './app'

run Brisk::App

So far so good. Now let's look into adding models and other routes into the mix.

Autoload

Similar to Rails, I like having one main app directory, containing a models, routes and views child dirs.

I use autoload to explicitly load in files (rather than using ActiveSupport's Dependencies). It looks like the following:

module Brisk

module Models

autoload :Post, 'app/models/post'

end

end

autoload differs from require in that it lazy loads modules the first time they're referenced, rather than at runtime. Now autoload is not without its caveats which you should understand before using it. It's not thread safe, and may even be deprecated in future version of Ruby. It's for this reason I'm slightly wary about suggesting people use it. However, it personally solves my needs just fine.

To get autoload working correctly, you'll also need to ensure that the current directory is in the app's load path. You can do this by appending the CWD to the $LOAD_PATH (aliased to $:). Add the following to app.rb:

$: << File.expand_path('../', __FILE__)

MVC

So our application has one main route: App. If we want to go about creating another route, we just need to mount it on App. Essentially, each route is its own separate application. For example, we could have a Posts route under app/routes/posts.rb (routes are always plural).

module Brisk

module Routes

class Posts < Sinatra::Application

error Models::NotFound do

error 404

end

get '/posts/:slug' do

@post = Post.first!(slug: params[:slug])

erb :post

end

end

end

end

Then we just have to mount Posts in App:

module Brisk

class App < Sinatra::Application

# ...

use Rack::Deflater

use Routes::Posts

end

end

If you take away one thing from this article, then this should be it. De-couple your application by splitting it up into lots of smaller applications mounted under one base. Believe me, this is the secret to keeping things simple and clean.

Sharing between routes

If we want to share some functionality between routes, say some configuration, we can use inheritance.

Let's define a Base route, which all the other routes inherit from.

module Brisk

module Routes

class Base < Sinatra::Application

configure do

set :views, 'app/views'

set :root, App.root

disable :static

set :erb, escape_html: true,

layout_options: {views: 'app/views/layouts'}

end

helpers Helpers

end

end

end

In the example above, we're setting up some basic :erb configurations (important for XSS security), and setting the route's CWD. Notice we're also importing a Helpers module which will contain global helpers.

Now we have this Base class, we can inherit from it in other routes to share its functionality. For example, if we wanted to have a authentication layer we could implement it as a Sinatra extension, import it into Base, and all our routes would have access to it.

Models

Database-wise I always choose Postgres. I've found, in the long run, document orientated databases aren't worth the hassle. Postgres is incredibly flexible, rock solid, and has never let me down. It's also pretty convenient because I host everything on Heroku and they have a great Postgres option.

For an ORM I like to use Sequel. In my opinion, it's hands down the best Ruby ORM out there, and strikes the right balance between too much magic and a good abstraction. Crucially the source code is readable and well written, something I check before using any new library.

I also use the project sinatra-sequel, which adds a nice DSL around setting up a database. For migrations, I have a few Rake tasks to help me.

namespace :db do

desc 'Run DB migrations'

task :migrate => :app do

require 'sequel/extensions/migration'

Sequel::Migrator.apply(Brisk::App.database, 'db/migrations')

end

end

For more information about Sequel's migrations, see the documentation.

Assets

I use CoffeeScript for JS and Stylus for CSS on the client side, and compile them using Sprockets. Even if you're not using a language that needs to be compiled, I recommend using an asset manager like Sprockets to give you concatenation and cache expiry.

Since Sprockets has great Rack support, integrating Sprockets and Sinatra is fairly straight forward. Just add another route called Assets which will serve up Sprockets compiled assets in development. In production, you can just pre-compile them and serve them statically.

module Brisk

module Routes

class Assets < Base

configure do

set :assets, assets = Sprockets::Environment.new(settings.root)

assets.append_path('app/assets/javascripts')

assets.append_path('app/assets/stylesheets')

end

get '/assets/*' do

env['PATH_INFO'].sub!(%r{^/assets}, '')

settings.assets.call(env)

end

end

end

end

I highly recommend turning on caching for Sprockets, which will make it much faster to use in development and in deploys. In development use Sprocket's FileStore, and in production I use Memcache. For more information, check out this article I wrote on speeding up deploys to Heroku.

ENV vars

I never hard-code passwords or API keys in the source code, or expose them in the GIT repository. Rather I use environmental variables. In development, I store test keys in a .env file, which is ignored by Git, and picked up automatically by the dotenv gem.

Conclusion

As mentioned previously, if you're interested in building applications in this style, check out the Trevi gem. Also if you want to check out the source code of a real application using this structure, Monocle is a good example.

You may be wondering why, if I've gone to all this trouble to create a scaffold, I don't just use an existing framework like Rails. My main motivation is to keep the stack as small as possible and customized to the task at hand.

At the end of the day, I like very simple abstractions and I like tinkering. I think the main contention point between differences in programmer's opinions is the amount of abstraction they're happy with. Sinatra happens to be at a good level for me.

Why startups should choose B2B

by Alex MacCaw

Business to business companies are back, and if you're thinking about building a startup I want to try and convince you to build a company that appeals to businesses (B2B) rather than one that appeals to consumers (B2C).

Let's start with some of the advantages that running a B2B gives you:

Immediate and impartial advice: Businesses won't sugar coat any feedback. They'll tell you exactly what their problems are, what they think of your service, and what they will pay for. I can't tell you how valuable this kind of feedback is.

Profitability: There's no better indication that you're on the right track than someone giving you money. The biggest perk of being a B2B is the near-immediate market validation. Just keep iterating until people pay you money. Getting a B2B profitable is a order of magnitude easier than a B2C. If you're solving a problem with a measurable benefit, companies won't hesitate to pay you.

Choice of funding: When profitable, you're in a much better position when it comes to raising money; you have a choice. You can choose to bootstrap the business and grow it organically, or you can choose to inject venture capital. It all depends on your goals. The key is that you have time to make an informed decision, and don't have to lose control and take the business in a direction you'd rather not just to keep it afloat. If you do decide to raise, it'll likely be on better terms.

Acquiring customers: Finding customers and converting them is that much easier, because you know who they are, where to find them, and they're generally willing to pay. You don't have to resort to growth hacking, huge advertising campaigns, building marketplaces and solving one-sided social graph problems. You can approach companies with traditional direct sales and marketing.

Realistic exits: Valuing a company with healthy revenues is much more straightforward than a highly leveraged consumer focused startup. Exits may be smaller, but they're more likely and you'll keep a bigger slice of the pie. Conversely with consumer startups you'll generally have to put all your chips on the table and bet large. As mentioned before regarding investment, profitability gives you the freedom of choice — you don't ever have to exit if you don't want to.

What's changed?

Traditionally it's been fairly difficult to break into the enterprise market due to prohibitively large development and sales costs. Not so these days — development and distribution costs are a fraction of what they once were, and companies are finally moving away from their protracted enterprise sales cycles.

This means that what were once startups' weaknesses have become their competitive advantage. As a startup, you can compete against larger corporations on cost, friendly support, beautiful design and development agility. In short, the product actually matters again! Startups and smaller companies can start to eat away at the dinosaurs.

On the surface of it B2B's may not be as attractive as consumer startups, or command their following in the tech press. However a company is what you make of it; it all comes down to having passionate customers, attractive design, a good culture and intelligent branding. Source control wasn't attractive until GitHub got into the scene, and credit card processing wasn't sexy until Stripe appeared.

The problem with emails from recruiters

by Alex MacCaw

Emails from recruiters have a fairly infamous reputation in the technical community, partly because of their often spammy nature, and partly due to a lack of interest in the jobs they're pitching.

The ideal recruitment email should basically be a pitch, motivating candidates to further explore the opportunity. Engineers are extremely fortunate--we're not generally in want of a job. To hire the best, you have to entice them away from other work.

Unfortunately many recruitment emails seem canned at best, automated to spam out to the widest audience possible. It's a wonder these emails work, if indeed they do at all. Looking back through my inbox, here's some of the mistakes I often see recruiters making:

- Canned, with only the name changed

- Asking people to email in their CV or resume

- Not mentioning the company name, only an unspecified 'client'

- Urging you to spam your friends with the opportunity

- Mention ninja, rockstars, or showing a general technical incompetence

- Advertising a job in country I'm not in, or for a language I don't use.

The problem stems from two very different worlds colliding, one technical, one not--there's no wonder it's a source of friction. Recruiters are trying to hire for jobs that they don't understand, let alone make technical evaluations for.

Let's take an email I received the other day (anonymized) as an example:

Hi Alex,

How are you? I just came across your profile and thought you could be a great fit for a company that I am recruiting for in San Francisco called FirstWorldProblemsFixed.

Not a great start. It doesn't look like any effort has been put into this--indeed my name seems to be the only customization in an otherwise canned email. There's no explanation of what the company is, or why I'd want to join.

We are looking for only the best to join this team. If you are a rock star ninja, please send your updated resume to me and let me know when you have some time for a quick chat so I can tell you more.

If the recruiter had done their homework, they'd just look at my work online rather than asking for a resume. Indeed, I don't even have a resume - an active GitHub account should be enough for most programming jobs. Also, what exactly is a rock star ninja?

If you're not interested, could you please share the open job on your channels anyways, mention it to your RoR friends, that would be so cool, thank you!

And they finish with a desperate plea to spam all my other friends.

Best, Jessica

Clearly this particular example is a bit of a straw man, and there are certainly better emails from recruiters. However I'm sure we can agree that the general trend is pretty abysmal.

The reality is that if you're cold emailing a candidate you're already at a big disadvantage. Referrals are the best method of recruiting bar none. Take advantage of your company's combined social network, a short email from a founder or engineer will do wonders.

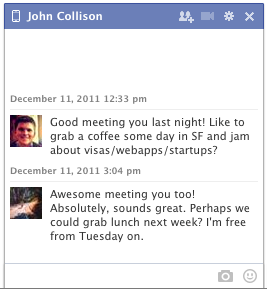

For example, here's the Facebook message I got from John which ultimately led to me leaving Twitter for Stripe. It's short, to the point, and referral based.

This is the kind of dialog we're trying to encourage at Sourcing.io, and we're aiming to raise the bar on technical recruiting. We are going to great lengths to ensure that recruitment offers are personal, of high quality, and ideally from someone you're already acquainted with.

This is a repost from an article I wrote on my personal blog in October.